In the screen printing industry, Silicone ink is known as the “difficult” ink. It is expensive, it has a short shelf life, and it requires mixing catalysts before every run.

Yet, if you walk into a luxury streetwear retailer—looking at brands like Fear of God, Off-White, or Palm Angels—almost every graphic printed on denim is Silicone.

Why do brands accept the higher production costs and technical headaches? It isn’t just about “quality.” It is about physics and perceived value.

Here is the technical breakdown of why high-end brands have standardized on Silicone for denim.

1. Physics: The “Elastomer” Advantage

The most practical reason is mechanical. Modern streetwear denim is rarely 100% cotton anymore; it is usually 98% cotton and 2% elastane (Spandex) for comfort.

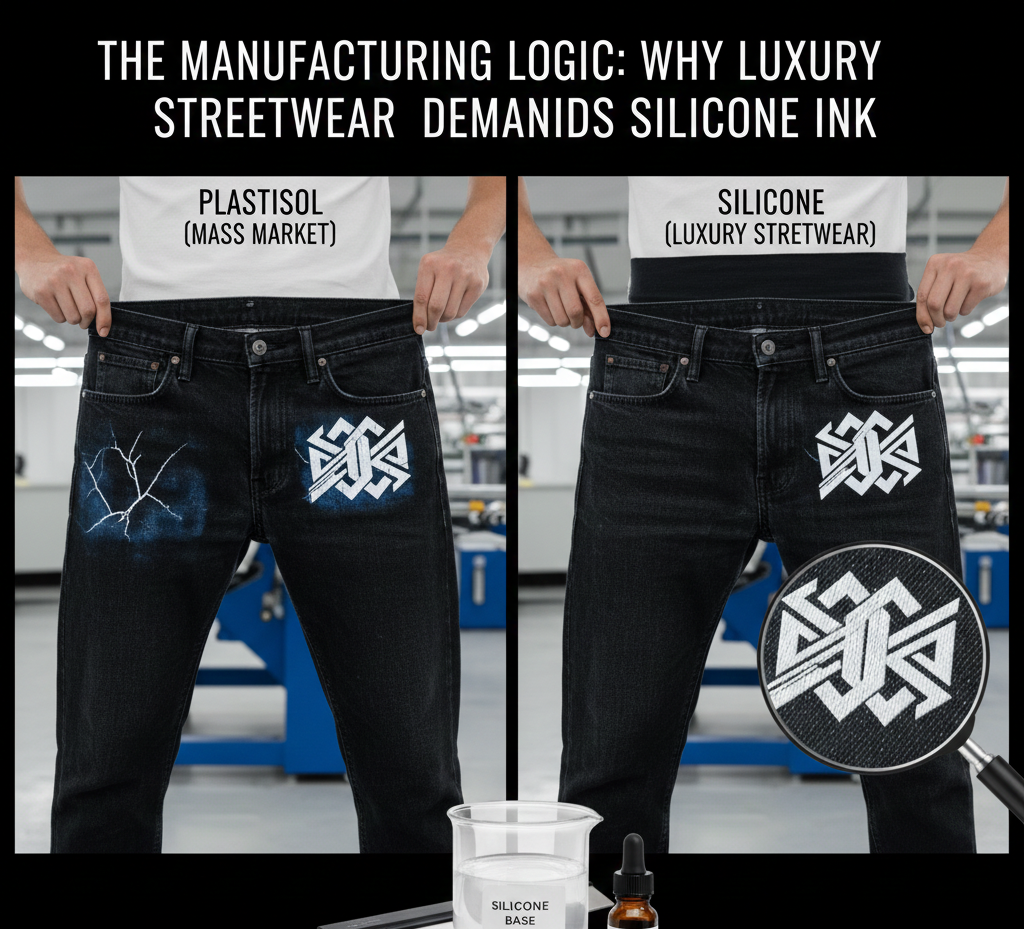

- The Plastisol Problem: Standard Plastisol ink is a thermoplastic resin. When it cures, it becomes a rigid plastic sheet. If you stretch the fabric, the ink does not stretch with it. It cracks.

- The Silicone Solution: Silicone is an elastomer (synthetic rubber). It has an elongation capacity of over 300%.

- The Result: When a consumer puts on a tight-fitting or baggy pair of jeans, the fabric stretches. The silicone print stretches with it and snaps back perfectly without fracturing. This prevents the “cheap” look of cracked logos after three wears.

2. Chemistry: The “Anti-Migration” Barrier

Printing white ink on dark blue indigo denim is a chemical nightmare. The indigo dye is unstable and turns into a gas under heat, penetrating the ink and turning it grey or light blue (Dye Migration).

While Plastisol requires heavy “Grey Blocker” underbases to stop this, Silicone has a natural chemical resistance to dye migration.

- Heat Tolerance: Silicone is cured at lower temperatures (with additives) or is naturally more resistant to the gases released by indigo.

- Opacity: Silicone has higher pigment load capabilities. A single hit of white silicone is often more opaque than two hits of white plastisol, resulting in that stark, bright white logo that pops against dark washes.

3. Aesthetics: The “Matte” Finish

In the current fashion cycle, Gloss = Cheap and Matte = Expensive.

Standard Plastisol ink naturally cures with a slight shine or gloss. To make it matte, printers have to add dulling agents, which can weaken the ink.

Silicone, by nature, cures to a dead matte finish. It looks industrial and architectural.

- High Density (3D): Because silicone is thick and holds its shape, printers can stack multiple layers to create a “High Density” (3D) effect that has sharp, 90-degree edges. Plastisol tends to “slump” or round off at the edges when built up high. The sharp edge of a silicone print looks like a manufactured rubber patch, not just painted ink.

4. The “Touch” Test (Perceived Value)

This is the commercial driver. When a customer picks up a $400 pair of jeans, they touch the logo.

- Plastisol: Feels like plastic or rough sandpaper. It feels like a t-shirt print.

- Silicone: Feels smooth, rubbery, and “grippy.”

This tactile difference is a subtle psychological trigger that justifies the high price point. It feels engineered rather than printed.

Comparison: The Cost of Quality

Why doesn’t everyone use it? The barrier is cost and skill.

| Feature | Standard Plastisol | Silicone Ink |

| Material Cost | $ (Low) | $$$ (3x – 4x higher) |

| Production Speed | Fast (Ready out of bucket) | Slow (Requires mixing catalyst) |

| Waste | Low (Ink can be reused) | High (Leftover ink hardens) |

| Skill Required | Beginner / Intermediate | Advanced |

| Retail Value | Mass Market | Luxury / Designer |

Silicone ink is not a stylistic choice; it is a manufacturing specification for stretch fabrics.

For streetwear brands producing baggy, heavy, or stretch denim, the switch to Silicone is a defensive move against cracking and dye migration, and an offensive move to increase the perceived value of the garment. It turns a graphic print into a structural component of the jeans.